What’s in a Slur? A New Play Searches for Answers

Jun 9, 2007

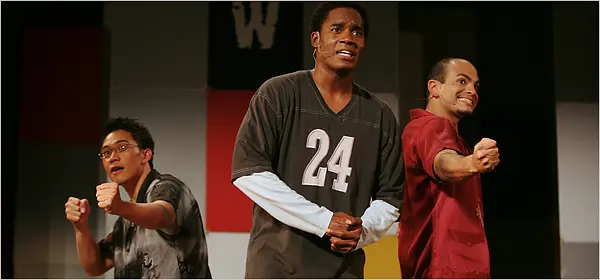

Credit: Heidi Schumann for The New York Times

Lest anyone think that a play with three ethnic slurs in its title is going to dance around the subject of race and the limits of tolerable discourse, be advised that the bombshells are hurled from its opening moments:

An Asian actor, dressed in blue Chinese pajamas, steps onstage chanting rhythmically, “CHINK-chink-chink, CHINK-chink-chink.” He is followed by a Latino actor, in flood pants and a do-rag, chanting the word “Wetback,” who is then followed by a strutting African-American actor in a floor-length red coat and feathered hat, chanting “Nigger,” over and over, in syncopation to the other slurs.

To the uncomfortable laughter of the audience, the Asian actor, Allan Axibal, notes that he has now hurled his slur 270 times.

“Man!” replies the Latino actor, Rafael Agustín, “You always have to overachieve.”

Opening its first major run this week — two months at the Ivar Theater in Hollywood — the comedy, whose three-word title consists simply of those racial slurs, seems remarkably well timed to land in the middle of the national discomfort zone.

In the age of Don Imus and Michael Richards, in light of the renewed scrutiny of hip-hop lyrics and shock-jock blabbermouths, “N*W*C,” as it is called for short, examines the power of timeworn taboos, attempting to deflate them through a frontal, often funny, assault.

The timing, however, is something of a coincidence, since the play has been touring the country for about two years, mainly on college campuses, where the three principal actors and writers — Mr. Agustín, Mr. Axibal and Miles Gregley — have tested and honed their material from Seattle to South Carolina to upstate New York.

They are close friends, former debate team champions who together attended community college and then the University of California, Los Angeles, and who set out to tell the story of race in contemporary America through their own life experiences with intolerance, immigration and integration.

“We said, ‘Let’s write about our own lives,’ ” recalled Mr. Agustín, 26. “We didn’t know if it would be that interesting, but it’s really resonated with people. There’s nothing like winning over an audience in Kentucky who doesn’t want to hear about the immigration debate.”

The result, so far, has been its own social experiment, according to the authors, who find audience members lined up to share their views after performances. At the first show at U.C.L.A., picketers ended up joining the ticket line to see what the play was about. The police told them neo-Nazis had threatened one performance in Olympia, Wash., while the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People sent out fliers condemning their use of the ethnic slur against blacks at another one.

Meanwhile, mainstream newspapers and radio stations have refused to take advertisements for the Los Angeles run, because the title is a trifecta no-no.

So why create a play guaranteed to offend all along the racial spectrum? “It’s not the words that are painful, it’s the racism behind them,” said Mr. Axibal, a 25-year-old of Philippine origin, sitting with his two friends at a quiet cafe at the Hilton Hotel in San Francisco, where they had flown in to perform at a national conference on race relations.

Mr. Agustín added: “These words substitute for our cultural identity — ‘I guess we’re this’ — and then self-hate starts happening. It wasn’t until I got to college that I started to appreciate my own culture.”

Mr. Axibal said: “If we’ve been called these words, then we have the right to confront them. That’s what the show is about.”

As the play suggests, they have been called those words. But the more painful aspects of racism had to do with the limits the outside world placed on them as talented young men with ambition and imagination who didn’t define themselves by race.

In the case of Mr. Axibal, it was the dejection he felt when told he could never be like Tom Cruise because he was Asian; his mother sympathetically suggested he have “the surgery” to make his eyes look more Caucasian. (“More cauc, less Asian,” he deadpans in the play.)

In the case of Mr. Gregley, 28, who grew up among white kids in Baldwin Park, near Los Angeles, it was the ridicule he endured when he told friends he admired the singer George Michael of Wham! and wanted to be like him. Then, when he was sent to Atlanta for a year at 13, he realized he also had to adjust to fit in among other African-Americans.

“It became: ‘Am I black enough? Am I wearing my pants low enough?’ ” he recalled.

And Mr. Agustín, a high achiever, was an illegal immigrant in this country for 14 years, which kept him from enrolling in the top California universities despite being accepted there. He eventually won a green card, which allowed him to transfer to U.C.L.A.

Oddly, the play originated in the more subtle racism of the entertainment world. When Mr. Agustín was a graduate student at U.C.L.A.’s School of Theater, Film and Television in 2003, he became frustrated when he was rejected repeatedly for leading parts in plays by Shakespeare and Tennessee Williams, directed by other students.

“One director said: ‘You’re fantastic. There’s this Latino play, you should audition for that,’ ” recalled Mr. Agustín, whose father was a doctor in Ecuador who ended up working at Kmart after moving to this country for economic reasons.

Mr. Agustín complained to the faculty — which, he says, reported back that the directors said they envisioned Brad Pitt-Jude Law types in the leading roles. He realized he would have to write something himself to showcase his talent.

He reached out for help from a mentor and former debate coach at Mount San Antonio College, the community college in tiny Walnut, Calif., where Mr. Agustín was a champion debater. The coach, Liesel Reinhart, and her boyfriend, Steven T. Seagle, helped shape the piece and suggested bringing in his former debate teammates, Mr. Axibal and Mr. Gregley.

At the time Mr. Gregley was doing stand-up comedy in his spare time, while Mr. Axibal was doing slam poetry in his. “The three of us sat down together one day and had a simple conversation about how we felt about the state of things,” Mr. Agustín recalled.

Mr. Axibal said: “We started telling each other the things we went through. Even as close friends, these were things that we never knew about each other. We’d all had experiences with these words.”

Over two years of performance in 24 states, “N*W*C” has shifted and evolved with practice and experience. They have added a Michael Richards joke. They have closely watched the immigration debate. They have had a white supremacist tell them their play changed his point of view.

They hope one day to bring the show to Broadway or parts nearby, and to spin it into a television show. Their attempt to write their way into a career has been a success, but it has also become a mission of sorts.

“People say to us: ‘You can’t stop doing this. You have to keep going,’ ” Mr. Gregley said.

Mr. Agustín chimed in: “We think, ‘The N.A.A.C.P. and the neo-Nazis are ticked off at us? We sure are bringing people together.’ ”

Read the full article here.